So today’s group meeting got a bit heated as Nafiz, Ashley, and Xiao touched on the finer points of how to cross validate. Machine learning people, your comments are welcome.

So I saw this Tweet from Michael Eisen a couple of days ago:

and those cows are destroying whatever gains clean energy creates https://t.co/DWRFj5x8Jj

— Michael Eisen (@mbeisen) September 3, 2016

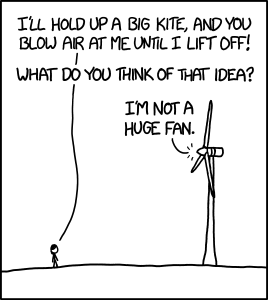

This was in reference to a Slate article by Dan Gross about how Iowa is leading the US in renewable energy, specifically wind-based. Having lived in Ames for over a year, I can tell you there is no shortage of wind in Iowa. There is no shortage of windmills either, but also there are quite a few cows. And cows are a serious source of methane, a greenhouse gas that is 25 times more potent than CO2.

So: does cow methane actually offset the greenhouse gas saved in Iowa by wind farms? Let’s check.

Coal, which is used in most Iowa power plants generates roughly 1kg CO2 for every 1kWh energy produced.

In 2015 Iowa generated 17,878,000,000 kWh from wind. That means 17,878,000,000 kg CO2 were not generated from coal. Since methane is a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent in trapping heat than CO2 that means that the equivalent of 715,120,000 kg of methane were not released to the atmosphere by using wind power.

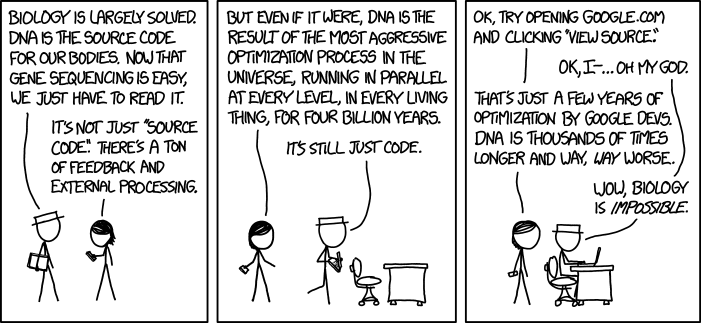

Obligatory xkcd

And now, to our bovine friends, of which roughly 3.9 million inhabit our fair state of Iowa.

Interestingly, dairy cows and beef cows have different methane emissions. A dairy cow is twice as gassy as a beef cow with 100.7 kg/year of methane from the former, and 50.5 kg methane/year for the latter. Iowa has about 3,000,000 dairy cows, and 940,000 beef cows. 3 mil dairy cows in Iowa generate 332,100,000 kg methane, and 940,000 beef cows generate 47,470,000 kg methane for a grand total of 379,570,000 kg methane / year. Which is about half (53%) of the emissions saved by windmills (715,120,000).

So: while cows in Iowa produce quite a bit of methane, they are definitely not “destroying whatever gains” generated by wind energy.

Moo.

TL;DR: NIH are scaling back funding on model organism databases, which will degrade annotation quality. This can have far-reaching implications in many aspects of biology and computational biology. There’s a letter you can sign electronically, please do. <http://www.genetics-gsa.org/

Dear Colleague,

I am writing to alert you to an important issue concerning the future of the Genome Ontology Consortium (GOC), but also all of the model organism databases (MODs). The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), which funds several of the MODs and the Gene Ontology (GO) Consortium, has announced there will be decreased funding for these resources over the next few years. A news article was published in Nature on Tuesday that reports on these changes, <http://www.nature.com/news/1.

The NHGRI has recently put forth a requirement that the GOC and MODs work more closely together with the aim of reducing infrastructure costs. The initial requirement is to create a shared web platform and data management system, and to use common tools and software. While this sharing has begun, the situation regarding long-term support of biomedical resources, and GOC in particular, is unclear. Current funding is down from previous years, and NHGRI’s plan is to continue this decrease with each subsequent year.

A group of leaders from the model organism research community has prepared a letter to NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins. In the letter, they strongly advocate for the maintenance of shared tools and infrastructure, but also stress the importance of the continued existence of independent community-focused resources. A prominent assemblage of signatories, including Nobel laureates, heads of scientific societies, and National Academy members have already endorsed this initiative. We hope to gather thousands of additional signatures and present the letter to Dr. Collins at The Allied Genome Conference (TAGC) in Orlando in mid-July. The letter can be easily signed on the website created by our partners at the Genetics Society of America (GSA), with your name and just two short questions about your location. These questions simply allow us to collate signatory numbers should NIH request a breakdown along these lines.

The Genetics Society of America website where the letter can be viewed and signed is at <http://www.genetics-gsa.org/

Your signature on the letter is telling the NIH that researchers need resources for their daily professional activities. Biomedical researchers use the GO website, tools, and expertly integrated information to be more productive in the design and analysis of their experimental work. Resources that curate literature provide a service that saves students, teachers, and researchers countless hours of tracing down information — hours that can be better spent doing the actual research. Simply said, biomedical resources aid the research conducted by the billions of dollars spent by NIH and others. We can use this letter to make the point to funding agencies around the world that biomedical resources need their active support.

I urge you to forward this email to the trainees in your lab, as we aim to collect signatures from all GO and MOD users who concur (for the question about NIH support, we can consider those who work in an NIH-funded lab to be NIH-supported). Finally, we encourage you to spread the word through your colleagues and via social media. We have every hope that a strong show of support, via an outpouring of signatures, will help shape the NIH plan to preserve the GO and MOD features that are most important to our collective research enterprise.

Sincerely,

Paul Thomas

University of Southern California

Judith Blake

Jackson Laboratory

Suzanna Lewis

University of California at Berkeley

Paul Sternberg

California Institute of Technology

J. Michael Cherry

Stanford University

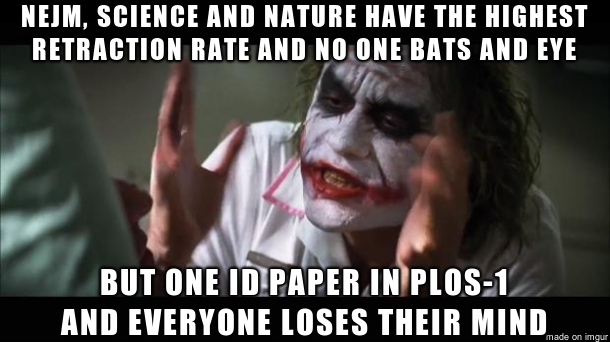

As everyone knows by now, PloS-1 published what seemed to be a creationist paper. While references to the ‘Creator’ were few, the wording of the paper strongly supported intelligent design in human hand development. A later statement from the first author seemed to eschew actual creationism, but maintained teleological (if not theological) view of evolution, and saying that human limb evolution is unclear. The paper was published January 5, 2016. However, it seemed not to get any attention. The first comment on the PLoS-1 site was on March 2, when things blew up on Twitter, quickly adopting the #handofgod and #creatorgate hashtags. (As far as I could tell, the paper URL has not been on Twitter before March 2, except for a single mention the day it was published.) On March 3, PLoS-1 announced that a retraction is in process.

Open Access is not broken

Probably the strangest reaction I have seen to #handofgod was in this article in Wired that examined the old trope that open access articles are poorly reviewed. I thought we were already beyond that, and that at least science writers have educated themselves on the matter. Review quality has nothing to do with the licensing of the journal! Tarring all OA publication with the same brush, without even saying why open access is relevant to this problem, is simply poor journalism.

Oh, and please stop confusing Open Source (for software licensing) with Open Access (for licensing research works). The two terms stem from the same philosophy of share and reuse, but they are best not conflated.

PloS-1 is not broken

Saying that publishing this paper shows the failure of PloS-1’s publication model, is like saying that because you read a news story about someone who got run over on the sidewalk, you will never walk on a street shared with cars ever again. PloS-1 publishes 30,000 papers per year. It took PloS-1 less than a month to retract from the publication time, and less than 48 hours from when this paper came on the social media radar. In contrast, it took Lancet 12 years to retract Andrew Wakefield’s infamous paper on vaccine and autism; a paper that was not just erroneous, but ruled to be fraudulent, and has caused incredibly more damage than a silly ID paper. Also, I am still waiting for Science to retract the Arsenic Life paper from 2010, and for Nature to retract the Water Memory paper from 1988. At the same time, I bet that only few of those who clamored they will resign from editing for PloS-1, will turn down an offer to guest edit for Science. Here’s an idea for all PloS-1 editors who are “ashamed to be associated with PloS one”: instead of worrying or self-publicizing on Twitter or PloS’s comment section, take up another paper to edit, and make sure it is up to snuff.

Or, you know what, go ahead and resign; if your statistical and observational skills are so poor as to not recognize your own confirmation bias, you should not be editing papers for a scientific journal.

Continue reading PLoS-1 published a “creationist” paper: some thoughts on what followed →

(New: the paper was recently published in Genome Biology!)

Long time readers of this blog (hi mom!) know that I am working with many other people in an effort called CAFA: the Critical Assessment of protein Function Annotation. This is a challenge that many research groups participate in, and its goal is to determine how well we can predict a protein function from its amino-acid sequence. The first CAFA challenge (CAFA1) was held in 2010-2011 and published in 2013. We learned several things from CAFA1. First, that the top ranking function prediction programs generally perform quite well in predicting the molecular function of the protein. For example, a good function predictor can identify if the protein is an enzyme, and what is the approximate biochemical reaction it performs. However, the programs are not so good in predicting the biological process the protein participates in: it would be more difficult to predict whether your protein is involved in cell-division, apoptosis, both, or neither. For proteins that can influence different phenotypes (pleiotropic), or have different functions in different tissues or organisms, the predictions may even be worse.

The Human PNPT1 gene has several domains involved in several functions. Some CAFA1 methods (circled letters, each circle is a different method) predicted some of the functions. But only method (J) predicted two specific functions (3′-5′ exoribonuclease activity and Polyribonucleotididyltransferase activity). Some methods predicted “Protein binding” and “Catalytic activity” correctly, but those are very non-specific functions. Reproduced from Radivojac et al. (2013) under CC-BY-NC.

So I saw Star Wars VII: “The Force Awakens” the other day. Great movie, which has mostly erased the shame of episodes I-III. Despite even more than the usual suspension of science, it’s a great SF flick.

(Major spoilers below! You have been warned!)

One mystery which will hopefully be resolved in the upcoming episodes is the origin of Rey. She is obviously strong with the force, using a Jedi mind trick on a stormtrooper (played by Daniel Craig!) to escape. Has visions related to the force, fights well with a lightsaber despite no previous training, and is a general badass. However, while it is pretty clear that Rey’s midi-chlorian count is violently high, it is not clear how she relates to the Force-inhabited family (of at all). One idea is that she might be Luke’s daughter, another that she may be a second offspring of Leia, making her a sister or half-sister to Kylo Ren.

Genetics can help us solve this problem. My assumption is that the Sith gene (sitH) is X-linked, recessively inherited. X-linked means that the gene sits on the X chromosome: so for someone to turn to the Dark Side, they need not only a high midi-chlorian count, but also a gene, which happens to sit on the X-chromosome. Recessively inherited means that for the genetic information to be expressed, women need two copies of the gene, but men only need one. Females would need two copies (alleles) of the sitH gene , one on each chromosome (X+/X+ which is why we see few Sith females). But a male inheriting an X chromosome containing a copy of sitH from his mother (X+/Y0) will inevitably turn to the Dark Side, because he does not have a second, x- chromosome to “block” the evil X+. (x- means a copy of X with no sitH gene Y0 means a Y chromosome which cannot carry a copy of the gene sitH).

Under this assumption, let’s examine the genotypes of the Skywalker family:

Anakin Skywalker (Darth Vader): X+/Y0 Anakin has a copy of sitH on his sole X chromosome. He fought for three miserable movies against going to the Dark Side, but failed and gave in to his genotype.

Leia Organa: X+/x- : Leia has to have one copy of sitH, since she has to receive one from Anakin, her father, who is X+. Thankfully, the other copy from her mother Padme Amidala is X-. sitH being recessive, Leia remained firmly in the Light Side.

Luke Skywalker: x-/Y0 Leia’s twin brother. Received the Y chromosome from Vader, and the x- copy from Padme.

Kylo Ren: X+/Y0 the new evil guy. Not quite a Sith Lord, but definitely embedded in the Dark Side. Leia and Han’s son, he received the X+ copy from mom, unfortunately.

Rey: X+/x- or x-/x-. If Rey is indeed Luke’s daughter, she would have received an x- copy from him. Assuming her mother is not from Jedi / Sith descent, that would mean that to be Luke’s daughter she is a x-/x-. Having an X+ copy would mean she got it from a parent who is carrying the X+ allele. Given the age differences, and possible range of parents, that would probably mean that Leia is her mother.

“You will remove these restraints, and PCR my saliva sample with a sitH primer”.

(More on X-linked recessive inheritance).

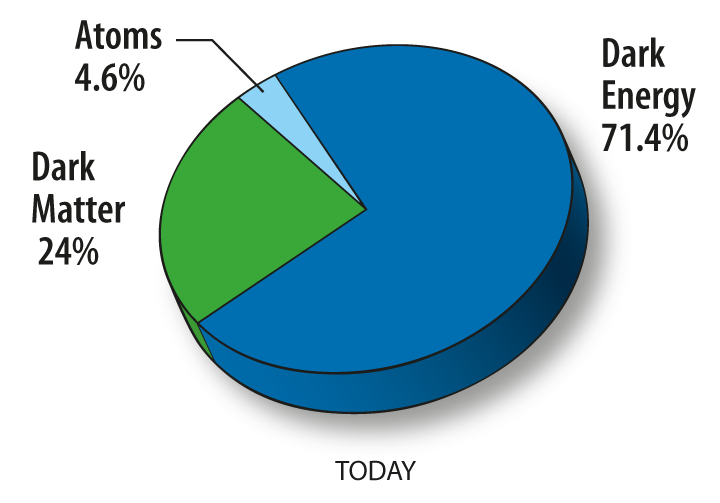

Dark matter is a proposed kind of matter that cannot be seen, but that we believe accounts for most of the mass in the universe. Its existence, mass, and properties are inferred from its gravitational effects on visible matter. The most favored hypothesis is that dark matter is not composed of baryons, the basic components of visible matter, but of completely different types of particles. In any case, while the actual nature of dark matter is a mystery, its effect on the universe is well-documented, and the term is quite precise in its usage and meaning.

Dark matter, dark energy and visible matter. From: http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/universe/uni_matter.html

Biological “dark matter” is quite a different thing, as the term is not original, but a metaphor taken from astronomy. As such, it has been used to mean various different things in different fields. In molecular biology, dark matter has been used to mean junk DNA, and non-coding RNA, among other things. In microbiology it has been used to describe the large number of microbes we are unable to culture and classify, and whose nature we mostly infer from metagenomic data. “Dark matter” has also been used for the shadow biosphere, a microbial world that does not feature any known biochemistry, and whose existence is only hypothesized.

I am uncomfortable with the use of the term dark matter metaphor in biology. First, this term is used to mean so many different things, it ends up meaning none of them. If someone tells me they work on biological dark matter, my first reaction is: “which one?”. Instead of being a clarifying shortcut, the use of this metaphor adds a layer of confusion. Second, as metaphors go, it is misused. With the exception of the shadow biosphere metaphor, we do understand what the various “dark matters” are composed of, and in many cases their effects on known biological mechanisms. The components of the various types of non-coding RNA are well-known to us: those are the same nucleotides that make up any RNA molecule. We may not understand the exact effects and how they work, but their nature (nucleic acids which may have information and catalytic ability) is not outside the scope of our current biological worldview. Similarly, in the case of junk DNA: yes, most of the DNA in some eukaryotes does not get transcribed or translated. Some of it may regulate gene expression, some (or a lot) of it is selfish DNA that simply replicates itself. But again, junk DNA is not dark matter as its composition is not alien to our understanding of biology, and there is no biological phenomenon that requires its existence to be explained. In fact, the opposite is true: we are not sure why some organisms have accumulated so much junk in their chromosomes, although we have some interesting hypotheses, and we are pretty sure there is no single underlying cause for the existence of junk DNA. As for the use of dark matter in microbiology: we probably have much to discover about microbial diversity, but it is no dark matter. We do not expect that new microbial species would be fundamentally different than those that we know of now: we expect them to be CHON life with mechanisms fundamentally similar to those we know of. That is not to say we are not hopeful of discovering new and exciting biochemistry and molecular biology in these undiscovered species. I am convinced that there are untold riches there! We may even discover new metabolites, new amino acids, maybe even new epigenetic or genetic mechanisms. But those would be still within the framework of known biochemistry. Even if we discover a radical new biochemistry, the second part of the metaphor does not hold: we do not need, at the moment, to assume a completely different microbial world to explain current life. This brings us to the realm of the shadow biosphere: the whole existence of a shadow biosphere, while intriguing, is hypothetical. It is not as if there are unexplained phenomena in biology that can only be explained by the existence of a shadow biosphere, and we have scant evidence of its existence. One day we may very well discover that we are sharing this planet with microbes of non-classical biochemistry. But, for now, we do not see any effects on our own biospehere that can only be explained by a shadow biosphere.

So is there dark matter in biology? Is there a phenomenon that cannot be explained unless we assume a mysterious new player that explains it?

Biology actually has a history of dark matter hypotheses. Biologists have always strived to explain how life differs from non-life, and for that they had to resort to any one of several mysterious “dark matter-like” (or, more appropriately, dark energy-like) explanations. Over time, the differentiation of life from non-life was explained by anything from the Aristotelian Final Cause to, most recently, vitalism: an unmeasurable force or energy that exists only in living creatures and differentiates a frog from a rock. All of these proposals were used to explain the apparent purposefulness of action, or teleonomy, in anything from microbes to humans. As we grew to understand biochemistry and the complexity of life, vitalism went out the window of respected science. Why? Do we understand the apparent purposefulness life displays? Not really, but we do not need to resort to an overarching force that explains it. Our (still highly imperfect) understanding of life is that organisms are emergent highly complex systems, whose apparent purposefulness is tied to evolution and their ability to self-organize and reproduce.

Is it alive?

So while there are plenty of unexplained phenomena in biology, at the moment there is really none that require the stipulation of a dark matter analogous to that which is in astronomy. Tempting as it may be, perhaps we should calm down on the use of the term dark matter in biology. Biology is confusing, complicated, and mysterious enough without it.

I recently attended a conference which was unusual for me as most of the speakers come from a computer science culture, rather than a biology one. Somewhat outside my comfort zone. The science that was discussed was quite different from the more biological bioinformatics meetings: the reason being the motivation of the scientists, and what they value in their research culture.

Biology is a discovery science. Earth’s life is out there, and the biologist’s aim is to discover new things about it. Whether it’s a new species, a new cellular mechanism, a new important gene function, a new disease or a new understanding of a known disease. Biology a science of observations and discoveries. It is also a science of history: evolutionary biology aims to find the true relationships among species, which is historical research.

In contrast, in computer science, the goal is the study and development of computational systems. Chiefly the feasibility, efficiency and structure of algorithms. So we have two different drivers here: in biology, we try to discover and/or “fill in the blanks” from what we see in nature. In computer science, we seek to understand and better perform computation.

When shall the twain meet? When the problem in biology is that of information processing, and when computer science can innovate in processing that information. Textbook case in point: a basic statistical model in biology today is that of sequence evolution. It states that, given two DNA sequences descended from a common ancestor, their descent can be depicted as a series of nucleotide deletions, insertions and substitutions. In fact, since historically a deletion event in one sequence can be viewed as an insertion event in another, the model actually narrows down to two types of historical events: the insertion/deletion event (or indel), and the substitution event. The model turns out to be a powerful tool, since it can be used to make predictions. Namely, if two DNA (or protein) sequences are found to have a relatively small number of indel and substitution events between them, they are considered homologous. The “relatively small number” is key here, and understanding when the number of steps is small enough to call the similarity between the sequences homology is a whole field unto itself. Finding homologous sequences is important for understanding evolutionary history, but not only for that. If the sequences are homologous, there is a good chance that the proteins they encode have similar functions, even in different organisms: which is the basis for the use of model organisms throughout biomedical research.

But at this point is where the biologist and the computer scientist may part ways. The biologist (here “biologist” = shorthand for “biological-discovery-oriented-researcher”) will continue to treat the sequence editing model as a tool for discovering things about life, such as finding a human homolog to a gene we know is involved in cancer in mice. The computer scientist (== “computational method investigator and/or developer”) may wish to refine the algorithm or create a new one to make the process faster, or more memory-efficient.

When do we have a problem? When researchers in one field do not understand the purview of the other, and seek a measure of simplicity where there is none. I was once told by a rather prominent virologist that “bioinformatics is all about pipelines”. I asked him what he meant by that and he basically said that all he really needs to have is a tool that will give him a result and a e-value “like BLAST”). When I said that statistical significance is, at best, one of several metrics that can be used to understand results, and that sometimes it does not coincide with biological significance or is simply inappropriate, he replied that “well, it shouldn’t be that way, as a biologist I need to know whether the result means something or not, and have a simple metric that tells me that”.

On the other hand, I had computer scientist claim that, since some proteins are a product fused from different genes (he meant different ORFs actually) , this phenomenon upends the definition of the gene, and that we should actually have a “new biology” which is not “gene centric”. To that, my reply was twofold: first, that biology is not “gene centric” any more than it is “ATP centric” or “photosynthesis centric”; and second, that the best description I can come up with for a gene is a “unit of heredity”. The reply I got was that this definition is not a good one since it is not rigorous, and too open-ended to be workable. (Note that I could not provide a definition for a gene, only a description.)

Both the virologist and the computer scientist were seeking simplicity or unequivocality in the “other’s” field where those are not to be found. The problem stems from a misunderstanding of each other’s fields, which they see only through the interface to their own. Biologists, which think in terms of discovery using hypothesis-driven research, would like to have tools that help test their hypotheses. A computer scientist would like to have a biological phenomenon that is clear-cut and therefore amenable to rigorous modelling. Both are flummoxed when they discover that ambiguity rests in their peers’ fields, even though they can totally accept it in their own.

What is to be done? First, learn more about each other’s fields. If you are a biologist using BLAST (and almost all are), please take care to read up on the statistics behind BLAST results. This will give you an idea of the different metrics BLAST provides you with, and what their meanings are. Do the same for the other software you use, and understand it is not just all about “pipelines”. If you are a computer scientist, and (for example) are interested in genomic annotation, please respect the 150 years* of thought invested in modern biology, that naturally keeps revising. However, understanding basic biological concepts is necessary before you go about arguing against what might be an unintentional strawman.

Also, try to listen more, and attend meetings outside your comfort zone. It seems I learn more from conversations in my “non-regular” meetings than in my “regular” ones. Of course, once the “non-regular” become my “regular” meetings I will learn less, so basically I may have to constantly shift my comfort zone. Then again, to me it seems like science is always poking and prodding outside one’s comfort zone.

———–

(*I picked the publication date of Origin of Species as an arbitrary start date, one might think this is conservative and go back even further).

Starting June 1, 2015, my lab is moving to Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa, and I’m very excited about this. I’ll be joining a growing cohort of researchers as part of a presidential “big data” hire the university has started a year ago. The research environment is superb, and there are some great bioinformaticians and genomics people there already (I’m not naming names, because there are too many, I’ll forget someone, and get people upset at me), as well as an excellent bioinformatics graduate program. I’ll be setting up shop as an Associate Professor in the Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Preventative Medicine. This means I’ll still get to be in an experimental microbiology department, which I like, and work with experimentalists and computational people all around campus. I’m honored that I was chosen for this position! Everyone at the university has been very helpful setting us up, and we’re not even physically there yet.

So if you are looking for a postdoc or graduate studies in computational biology, and you and are interested in bacterial genome evolution, document mining, protein function prediction, animal, human or soil microbiome, (among other things), I’m hiring. Ames, Iowa has been ranked as of the best places to live in the US: what are you waiting for? Graduate students: please apply through the Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Graduate Program, and/or contact me directly at Friedberg.lab.jobs at gmail ‘dot’ com. Postdocs: see ad below.

The Friedberg Lab is recruiting postdoctoral fellows to several newly funded projects. The lab is relocating to Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa as part of a university-wide Big Data initiative. Iowa State is a large research university with world-leading computational resources, and a strong highly collaborative community of bioengineering, bioinformaticians, and life science researchers.

The successful candidates will be joining the lab at the College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Veterinary Microbiology. Areas of interest include: bacterial genome evolution, gene and protein function prediction, microbial genome mining, animal and human microbiome, and biological database analysis.

These are bioinformatics postdoc positions, and the successful applicants would be required to perform research employing computational biology skills.

Requirements: A PhD in microbiology, bioinformatics, or a related field. A strong publication record in peer-reviewed journals. Strong programming skills; strong oral and written communication skills in English; Strong domain knowledge of molecular biology. Salary is competitive and commensurate with experience. The Friedberg lab is a computational biology lab equipped with high-end cluster computers and bioinformatics support.

Ames, Iowa is constantly ranked as one of the best places to live in the US, and has received numerous awards for being a progressive, innovative and exciting community with high affordability and high quality of life.

Candidates should send a C.V. and statement of interest as one PDF document, and have three letters of reference sent independently by their authors to Dr. Iddo Friedberg at Friedberg.Lab.Jobs “at” gmail dot com. Screening of applications begins immediately and will continue until the positions are filled. The positions are expected to start on or after June 2015.

All offers of employment, oral and written, are contingent upon the university’s verification of credentials and other information required by federal and state law, ISU policies/procedures, and may include the completion of a background check. Iowa State University is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action employer. All qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, age, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, genetic information, national origin, marital status, disability, or protected veteran status, and will not be discriminated against. Inquiries can be directed to the Director of Equal Opportunity, 3350 Beardshear Hall, (515) 294-7612

If you haven’t read the transcript of Sean Eddy‘s recent talk “On High Throughput Sequencing for Neuroscience“, go ahead and read it. It’s full of many observations and insights into the relationships between computational and “wet” biology, and it is very well-written. I agree with many of his points, for example, that sequencing is not “Big Science”, and that people are overenamored with high throughput sequencing without understanding that it’s basically a tool. The talk, posted on his blog, prompted me to think, yet again, about the relationships between experimental and computational biology. A few things in this talk rubbed me the wrong way though, and this is my attempt to put down my thoughts regarding some of Eddy’s observations.

One of Eddy’s main thrusts is that biologists doing high throughput sequencing should do their own data analyses, and therefore should learn how to script.

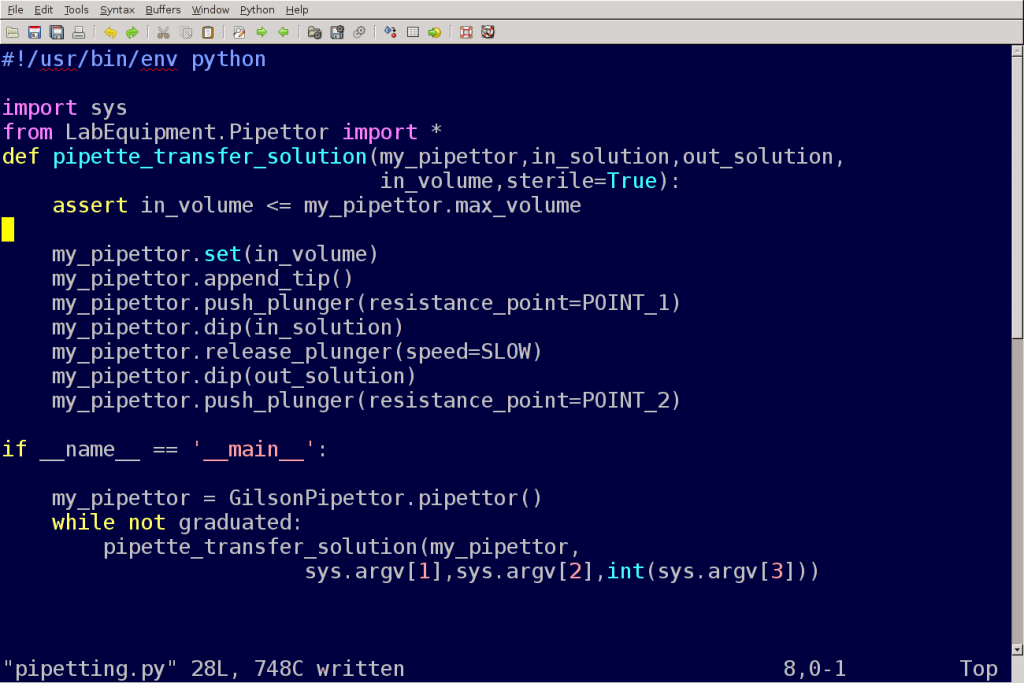

The most important thing I want you to take away from this talk tonight is that writing scripts in Perl or Python is both essential and easy, like learning to pipette.

There are two levels to this argument, I actually disagree with both: first, scripting and pipetting are not the equivalent in the skill level they require, the training time, the aptitude, the experience required to do it well, and the amount of things that can be done wrong. It may very well be that scripting is a required lab skill in terms of needs in the lab, but it is not as easy to learn to do proficiently as pipetting. (Although pipetting correctly is not as trivial as it sounds.)

But there is a deeper issue here, bear with me. Obviously, different labs, and people in those labs, have different skill sets. After all, it would be surprising if the same lab to was proficient in two completely disparate techniques, say both high-resolution microscopy and structural bioinformatics. We expect that labs specialize in certain lines of research, the consequent usage and/or development of certain tools, and as a result the aggregation of people with a certain skill sets and competencies in that lab. There are excellent biologists who do wonders with the microscope in terms of getting the right images. Then there are others who have invaluable field skills, or animal handling, primary cell-culture harvesting and treatment, growing crystals, farming worms, and the list goes on. All of those require training, some require months of experience to do right, and even more years to do well. All are time consuming, both in training and in execution, and all produce data, including, if needed (and sometimes not-so-needed) large volumes data. Different people have different aptitudes, and if a lab lacks a certain set of skills to complete a project, it is not necessarily a deficiency. It may be something that can be filled through collaboration.

Continue reading Why scripting is not as simple as… scripting →

- Unlock the secrets of animals that survive freezing: a crowdfunded science project to sequence the genome of the North American wood frog. Thirteen days to go!

- Why information security is a joke.

- This week was Open Access week. While many researchers support the idea of Open Access, few see it as a consideration for publication. Also, there is the problem of Open Access publication fees being regressive.

- An illustrated book of bad arguments. Very useful.

- Evolution explained clearly, via these beautiful videos.

- Lior Pachter on the two-body opportunity.

- Finally, I’ll put this image here. When you see it…

A question to genome annotators out there. I need a simple genome annotator for annotating bacteriophage genomes in an undergraduate course. Until now, we used DNAMaster but for various reasons I would like to move away from that. Here’s what I need for class:

1. Annotate a single assembled linear chromosome, about 50,000 bp, 80-120 genes, no introns (it’s a bacteriophage). Annotation consists of ORF calling and basic functional annotation (can be done in conjunction with BLAST / InterProscan etc).

2. Simple learning curve, these are undergraduates with no experience in the field.

3. Preferably Linux compatible

4. Can read FASTA, GenBank, GFF3

5. Output in a standard format, i.e. GenBank / GFF3.

6. Simple installation, preferably no unwieldy many-tabled databases.

I’ve been playing with Artemis using a Glimmer3 annotated genome and it seems OK so far, but what else is out there?

Please comment here and/or tweet @iddux with your ideas. Thanks!

Tweet to @iddux

Scammers are cashing in on the ebola scare. The news media is cashing in on the ebola scare. Politicians are cashing in on the ebola scare. Unfortunately, neither international healthcare nor biomedical research are cashing in on the ebola scare.

I found the first software patch. Seems pretty robust.

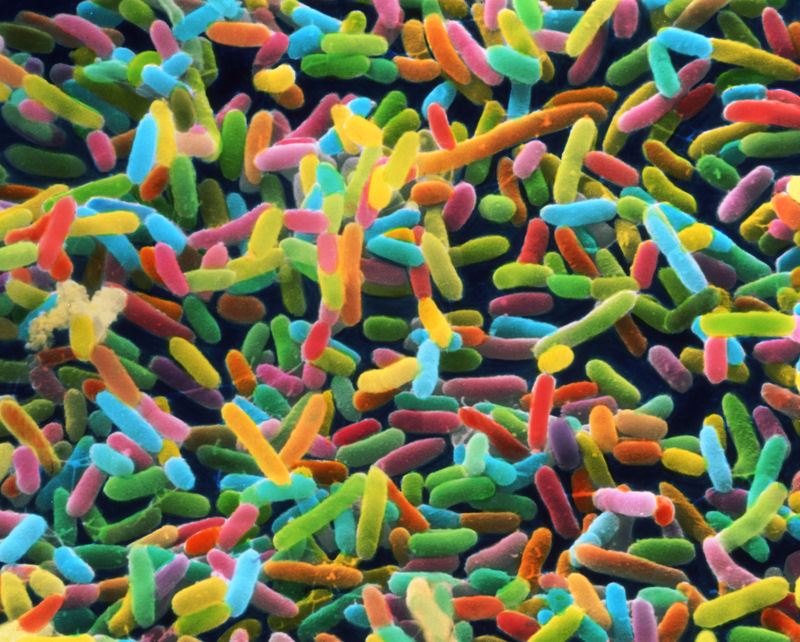

Diet can influence certain autoimmune diseases via gut microbes. Also, artificial sweeteners can make you fat via your gut microbes. Is there anything our gut microbiomes cannot do?

The Nobel prize for chemistry was awarded for bypassing the Abbe diffraction limit, enabling high resolution light microscopy. Cue the beautiful pics:

The actin filaments (purple), mitocondria (yellow), and DNA (blue) of a human bone cancer cell are elucidated using structured illumination microscopy, a related super high-resolution fluorescence microscopy technique. Source: NIH, Dylan Burnette and Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health